- Ancient Potter Reveals Genetic Mix

- Overcoming Preservation Challenges

- Questions Remain

Scientists have sequenced the oldest complete human genome from ancient Egypt, revealing genetic ties between early Egyptian civilization and Mesopotamia that date back nearly 5,000 years. The DNA, extracted from a potter who lived between 4,500 and 4,800 years ago, shows that ancient Egyptians carried ancestry from both North Africa and the Fertile Crescent region of West Asia.

The research, published Wednesday in Nature, represents the first whole genome sequenced from ancient Egypt and provides genetic evidence for cultural and population connections that archaeologists had previously only inferred from trade goods and artistic styles.

Researchers from the Francis Crick Institute and Liverpool John Moores University extracted DNA from the tooth of an individual buried in Nuwayrat, a village 165 miles south of Cairo12. The man lived during Egypt's Old Kingdom period, an era marked by political stability and the construction of the Great Pyramid of Giza.

Analysis revealed that 80 percent of his ancestry traced to ancient North African populations, while 20 percent linked to the eastern Fertile Crescent, including ancient Mesopotamia and neighboring regions3. The individual lived to between 44 and 64 years old, an advanced age for his time, and stood about 5 feet 2 inches tall with brown hair and brown eyes4.

"This individual has been on an extraordinary journey," said Linus Girdland-Flink, senior author and lecturer at the University of Aberdeen1.

The breakthrough comes four decades after Nobel Prize winner Svante Pääbo first attempted to extract ancient DNA from Egyptian remains12. Egypt's warm climate typically prevents DNA preservation, but this individual's burial in a ceramic pot within a rock-cut tomb created conditions that allowed genetic material to survive.

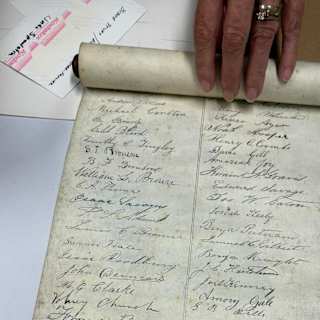

The remains had survived bombing during the London Blitz while housed at World Museum Liverpool, after being donated by the Egyptian Antiquities Service to British archaeologists in 19021.

Previous attempts to sequence ancient Egyptian DNA had yielded only partial genomes from three individuals who lived much later, between 1400 BCE and 400 CE3. Those studies found that modern Egyptians have more sub-Saharan African ancestry than their ancient predecessors4.

Population geneticist Harald Ringbauer of the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology, who was not involved in the research, noted the study's limitations. "We don't have ancient DNA to compare this to, so we can't know how much of their ancestry is local," he told DW1.

The research raises questions about when populations with Levantine ancestry first introduced agriculture to Egypt from the Fertile Crescent, according to Ringbauer1.