- The Discovery

- Historical Context

- Current Implications

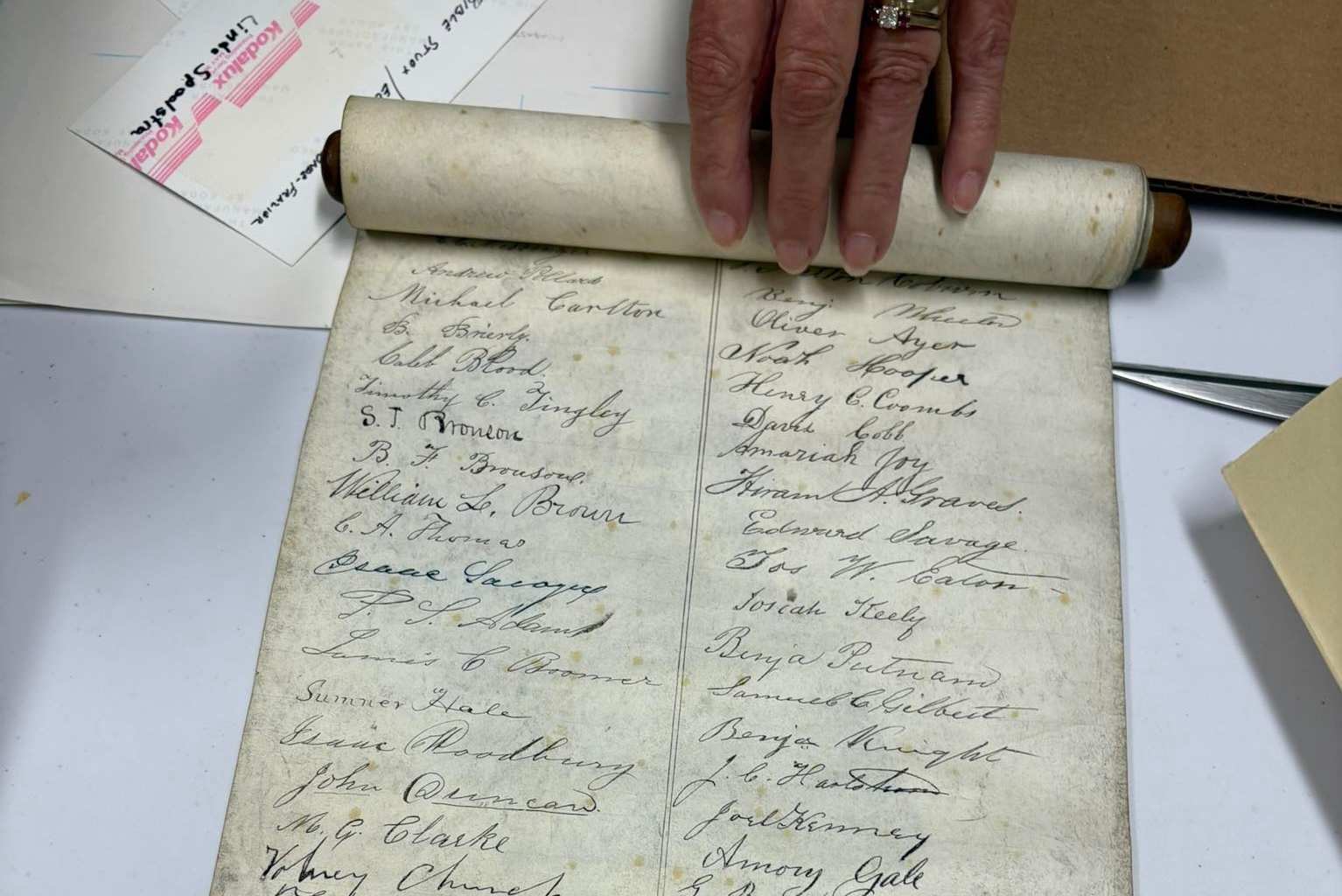

A retired teacher volunteering at a Massachusetts archive has uncovered a lost piece of American religious history: a 178-year-old document signed by 116 Baptist ministers condemning slavery that had been missing for more than a century.

Jennifer Cromack made the discovery in May while sorting through 18th and 19th century materials at the American Baptist archive in Groton, Massachusetts. The find resolves a decades-long search by church historians who feared the anti-slavery declaration had been lost forever.

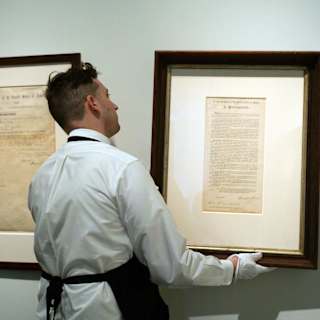

Cromack found the 5-foot-long handwritten scroll in pristine condition inside a slim box among historical journals1. The document, titled "A Resolution and Protest Against Slavery," was adopted March 2, 1847, in Boston1.

"I was just amazed and excited," said Cromack, who volunteers at the archive after retiring from teaching1. "We made a find that really says something to the people of the state and the people in the country."

American Baptist officials had searched for the document at Harvard and Brown universities and other locations without success1. The last known copy appeared in a 1902 history book1.

Rev. Diane Badger, who oversees the archive, called it the "Holy Grail" of abolitionist-era Baptist documents1.

The document emerged during a pivotal moment in American religious history. It was signed two years after slavery split the Baptist denomination in 1845, when southern Baptists formed the Southern Baptist Convention after northern Baptists prohibited slave owners from becoming missionaries1.

The ministers wrote they could "no longer be silent" after witnessing "a growing disposition to justify, extend and perpetuate their iniquitous system"1. The document declares slavery "an outrage upon the rights and happiness of our fellow men, for which there is no valid justification or apology"1.

Deborah Bingham Van Broekhoven, executive director emerita of the American Baptist Historical Society, said many northern Americans at the time were "undecided" about slavery and reluctant to speak out1.

"Most Baptists, prior to this, would have refrained from this kind of protest," Van Broekhoven said1. "This is a very good example of them going out on a limb and trying to be diplomatic."

Badger is now researching which ministers signed the document and which declined, creating a database of the churches they served1. Among the signatories was Nathaniel Colver of Boston's Tremont Temple, one of the nation's first integrated churches1.

Rev. Kenneth Young, whose predominantly Black church in Haverhill was founded by freed slaves in 1871, called the discovery inspiring1.

"It follows through on the line of the abolitionist movement and fighting for those who may not have had the strength to fight for themselves against a system of racism," Young said1.