- Skulls Tell Story of Urban Adaptation

- Museum Collections Enable Time Travel

- Broader Urban Evolution Pattern

Chicago's urban rodents are evolving in real time, developing altered skull shapes as they adapt to city living over the past century, according to research published today in the journal Integrative and Comparative Biology.

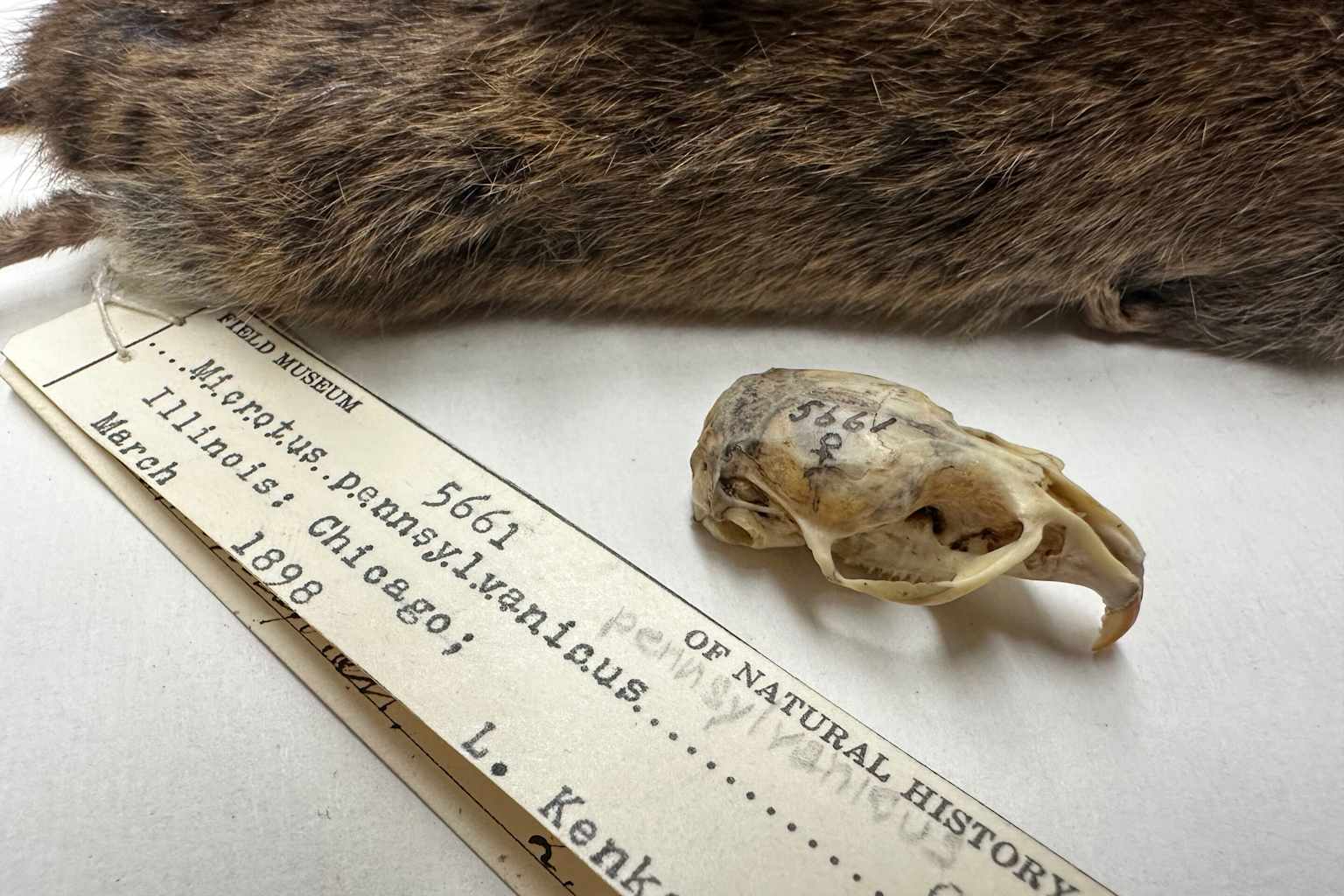

Scientists at the Field Museum analyzed skulls from 132 chipmunks and 193 voles collected over 125 years and found measurable changes linked directly to urbanization rather than climate shifts, providing rare documentation of rapid evolutionary adaptation to human-dominated environments.

Chipmunks living in the Chicago area developed larger skulls but smaller teeth over the past 100 years, changes researchers attribute to dietary shifts toward softer, human-related foods12.

"Over the last century, chipmunks in Chicago have been getting bigger, but their teeth are getting smaller," said Bruno Feijó, a study author, according to Popular Science. "We believe this is probably associated with the kind of food they're eating. They're probably eating more human-related food, which makes them bigger, but not necessarily healthier"12.

Voles showed different adaptations, with smaller auditory bullae—bone structures housing the inner ear. "We think this may relate to the city being loud—having these bones be smaller might help dampen excess environmental noise," said Stephanie Smith, a mammalogist at the Field Museum2.

The research leveraged the Field Museum's extensive specimen collection, with study co-authors Alyssa Stringer and Luna Bian measuring skull dimensions and creating 3D scans of select specimens1.

"Museum collections allow you to time travel," Smith said in a statement. "Instead of being limited to studying specimens collected over the course of one project, or one person's lifetime, natural history collections allow you to look at things over a more evolutionarily relevant time scale"1.

The team used satellite imagery dating to 1940 to quantify urbanization levels and correlated this data with morphological changes. Climate variations did not explain the skull alterations, but urbanization patterns did12.

The Chicago findings align with growing evidence of rapid urban evolution documented in cities worldwide. Previous research has shown similar adaptations in New York rats, which developed longer noses and shorter teeth between 1890 and 20101.

These changes represent examples of evolution occurring over decades rather than millennia when species face dramatic environmental pressures, though Smith cautioned against viewing the adaptations as wholly positive.

"These voles with smaller ear bones and chipmunks with smaller teeth are proof of how profoundly humans affect our environment and our capacity to make the world harder for our fellow animals to live in," she said2.